|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jean-Christophe Nebel

| My Popular Science Articles

|

|

January 25, 2022 1.45pm GMT

When the collapse of Zimbabwe’s electricity grid on December 14 2021 plunged most of the country into a blackout, Zimbabweans feared that they would have to spend Christmas in the dark. Much to their relief, two days later, the utility company restored a major power station and announced that there would be “minimal scheduled power cuts during the festive season”.

Unfortunately, due to weak and stressed power grids, outages are common in sub-Saharan African countries. Those who can afford it tend to invest in backup systems to ensure access to electricity.

Despite their high operational and environmental costs, diesel generators have proved the most popular choice. Unfortunately, the alternative – using renewable energy sources as a backup – is often seen as unreliable, since wind and sunlight are inherently intermittent.

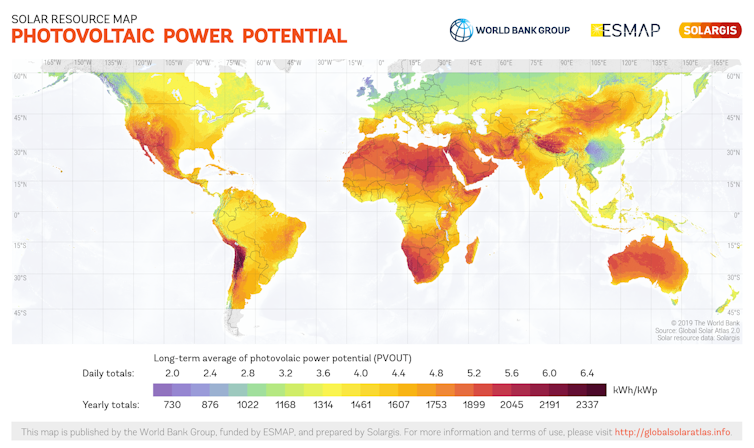

Yet sub-Saharan Africa is one of the regions with the most solar energy generation potential in the world, thanks to its relatively low cloud cover and high sunlight intensity. That means ways to reliably harvest this free, clean solar energy to power the grid without pollution are desperately needed.

Along with engineers from Ulster University, we’ve developed an intelligent solar backup system powered by artificial intelligence (AI) to support sub-Saharan Africa’s utility grids.

Our system is connected both to the grid and to a battery that can store electricity to back up the household where necessary. Since it’s designed for a region where individual electric water heaters are commonly used – in fact, they account for up to 40% of total household electricity consumption – the system also includes a solar hot water device, which uses solar radiation to directly pre-heat water without needing electricity.

To ensure that the backup system reliably provides electricity, an autonomous AI-based control system takes charge of battery usage.

By analysing the expected amount of energy produced by the solar panels and electricity needed by the household alongside the typical frequency and duration of blackouts, the AI makes sure that enough backup electricity is available in the battery at any moment by storing more during periods of high solar intensity. When the battery is full, that surplus electricity can be used to heat water or can even be sold back to the grid.

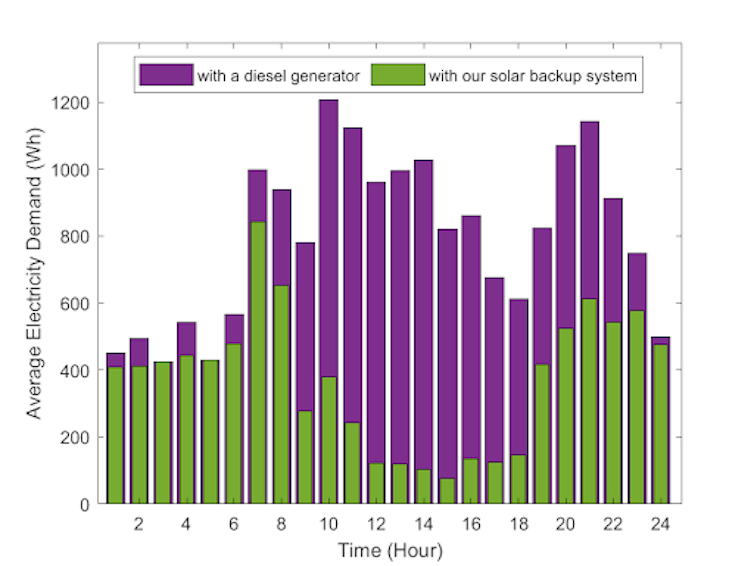

Using data collected from households in both Zimbabwe and Botswana, simulations comparing our intelligent solar backup system with a standard diesel generator demonstrated the superiority of our solar solution.

First, our system meets strict electricity reliability and hot water temperature parameters: meaning it’s guaranteed to work well when needed. Second, the lifetime costs of its installation, maintenance and use are around 25% lower than those of its diesel counterpart.

Third, it’s able to cut reliance on the grid during peak electricity usage hours. Importantly, this reduces stress on the grid and makes power outages less frequent. And fourth, this environmentally friendly solution cuts harmful greenhouse gas emissions from burning diesel.

Unfortunately, making solar-based backup systems in sub-Saharan Africa the norm faces a major obstacle. Their initial cost is six times higher than that of an equivalent diesel-based system: around £7,200 compared with £1,200.

The amount of this initial investment is likely to put many households off, especially those with lower incomes. Here’s where governments and utility companies will have to step in to provide loans or grants, helping everyone to access this technology.

Despite the disappointing outcome for many African nations of the recent UN climate change conference COP26, developed nations have promised to at least double their climate adaptation finance to developing countries by 2025. Hopefully, some of that money will be invested in solar-based backup systems, silencing the intense, familiar hum of diesel generators in sub-Saharan Africa.![]()

By Masoud Salehiborujeni, Senior Research Associate in Computing Science, University of East Anglia; Eng Ofetotse, Lecturer in Built Environment, Kingston University, and Jean-Christophe Nebel, Professor in Computer Science, Kingston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.